HOW TO TAKE RUSSIA BEFORE THE CHINESE DO IT: CAPTURE VLADIVOSTOK FIRST

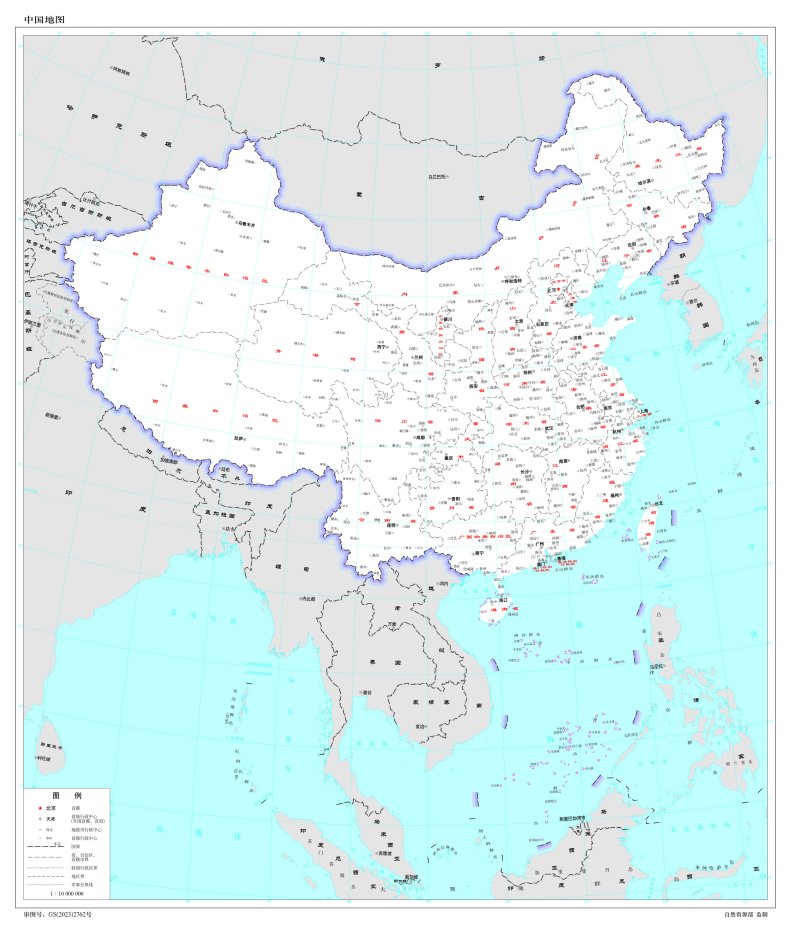

A new map of China's national borders has sparked protests from governments in Asia after its boundaries drew in the territories of its neighbors—including a small chunk of Russia.

The map, published on Monday by China's Ministry of Natural Resources, lays claim to disputed land on its southern border with India and encompasses all of Taiwan. Off its southern coast, Beijing's so-called "dashed line" captures huge tracts of the South China Sea, where islands, reefs and maritime zones are contested by half a dozen countries.

Beijing's longstanding territorial claims on its periphery aren't new. Under Chinese leader Xi Jinping, however, China has employed its growing hard power to consolidate its ambitions. In recent years, its neighbors have also faced the ramped-up presence of the Chinese coast guard.

Russia

Moscow and Beijing put aside their centuries-old boundary disagreements for the sake of political stability two decades ago. The last territorial settlement, finally ratified by the parliaments of both nations in 2005, resolved their shared eastern border, now under renewed scrutiny because of China's map service.

Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island, or Heixiazi, sits at the confluence of two border rivers, and ownership is legally shared between the two countries. China's official map paints the entire 135-square mile piece of strategic land into its easternmost territory.

The Kremlin has yet to comment on the map, which Beijing said was compiled using "national boundaries of China and various countries in the world."

Russia's Foreign Ministry didn't return an emailed request for comment.

India

Xi and Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India met days earlier, seemingly cordially, at the recent BRICS summit in South Africa, and China's map controversy comes two weeks before they are set to meet again in New Delhi for the upcoming Group of 20 forum.

The Indian government and at least one lawmaker were the first to respond to what they considered a cartological land grab of India's northern state of Arunachal Pradesh, at the eastern end of the 2,100-mile disputed border commonly known as the line of actual control.

Beijing considers the region part of Tibet and announced new Chinese place names there in April. Its map also includes Aksai Chin in the west, controlled by China but claimed by India.

"We have today lodged a strong protest through diplomatic channels with the Chinese side on the so called 2023 'standard map' of China that lays claim to India's territory," Arindam Bagchi, a spokesperson for India's External Affairs Ministry, said on Wednesday.

"We reject these claims as they have no basis. Such steps by the Chinese side only complicate the resolution of the boundary question," Bagchi said.

Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, India's foreign minister, called Beijing's move "an old habit." He told Indian broadcaster NDTV: "This government is very clear what our territories are. Making absurd claims doesn't make others' territories yours."

"India cannot afford to remain a mute spectator to such Chinese activities," said defense analyst Ashok Kumar, a retired major general of India's armed forces.

"India has to re-strategize to counter such actions in a proactive manner. It will be ironic to host the Chinese premier as part of the G20 summit when such an action has been taken just before this meet,"

The map shows new territorial borders, but the land grab has sparked protest from India, Malaysia and others MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES, CHINA

South China Sea

"A correct national map is a symbol of national sovereignty and territorial integrity," Li Yongchun, a senior resources ministry official, said of the newly released map, on which 10 dashes can be seen encircling the entirety of the South China Sea.

"The publicity and education of national territory awareness is an important content of patriotic education and an integral part of ideological work in the new era," Li said. "Maps, text, images and paintings can all describe national territory, but maps are the most common and intuitive form of expression of national territory."

Malaysia was the first of the littoral states on the energy-rich sea to come out in opposition to the Chinese map, which claims disputed features and most of the country's exclusive economic zone. International law recognizes a state's right to the maritime resources within its EEZ, which extends up to 200 nautical miles from the coastline.

"Malaysia does not recognize China's 2023 standard map, which outlines portions of Malaysian waters near Sabah and Sarawak as belonging to China," the Malaysian Foreign Ministry said in a statement. "Malaysia is not bound to China's 2023 standard map in any way."

"Malaysia is of the view that the South China Sea issue is a complex and sensitive matter. It must be handled in a peaceful and rational manner through dialogues and negotiations based on international laws, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)."

Tensions simmer between Poland and Belarus after incursion reported

I'm a Mormon on OnlyFans

The West isn't buying into China's year of diplomacy

Russian forces unable to return Ukrainian fire in key area: ISW

The Philippines—frequently blockaded by China's coast guard vessels while attempting to resupply a Manila-held outpost in the Spratly Islands—said its foreign affairs department would lodge a diplomatic protest because the map "infringes upon the sovereignty, the sovereign rights and the territorial integrity of the Philippines," according to Jonathan Malaya, the assistant director of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.'s National Security Council.

Beijing's extensive maritime claims in the region were roundly rejected in 2016 after the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled in Manila's favor in Philippines v. China. The Chinese government refused to participate in the case and has never recognized the tribunal's verdict.

China's Foreign Ministry said the map publication was "a routine practice in China's exercise of sovereignty in accordance with the law." Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin said on Wednesday: "We hope relevant sides can stay objective and calm, and refrain from overinterpreting the issue."

Indonesia considers itself a non-claimant when it comes to physical territory in the South China Sea, but it remains in dispute with China over fishing rights in the Indonesian EEZ. Its Foreign Ministry said on Thursday that depictions of territorial boundaries should comply with UNCLOS.

The governments of Brunei and Vietnam didn't return separate written requests for comment.

Taiwan

Taiwan's inclusion in the Chinese map would have surprised few. Beijing maintains a long-running claim to the democratically government island, whose Republic of China government retains control over Taiwan proper as well as a number of outlying island groups, including two off China's east coast.

Taipei has spent decades rebuffing Beijing's sovereignty claims but has only recently hiked up its defense spending to meet China's enlarged military footprint in and around the Taiwan Strait. The geopolitical and geoeconomic ramifications of any move to take the island by force aren't lost on Taiwan's neighbors, or its backers in the United States.

Jeff Liu, a spokesperson for Taiwan's Foreign Mionistry, told reporters on Wednesday that "the People's Republic of China has never ruled Taiwan. That is the fact and the status quo universally recognized by the international community."

"Regardless of how the Chinese government distorts its claims to Taiwan's sovereignty, it cannot change the objective reality of our country's existence," Liu said.

Japan

China and neighboring Japan have a long history of disagreements. This week, a renewed war of words followed Beijing's decision to ban all Japanese seafood products in response to Tokyo's discharge of diluted waste water from the Fukushima nuclear plant, which was damaged by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

But just northeast of Taiwan in the East China Sea, barely visible on China's new map, lies the disputed Senkaku Island group, which China calls Diaoyu and Taiwan claims as Diaoyutai. The uninhabited islets are under Japanese administration—and protected by a U.S. defense treaty.

The territorial dispute, which Taipei now rarely engages in due to warming ties with Tokyo, flared up a decade ago when the Japanese government nationalized the islands. Since then, China's largest maritime law enforcement ships—some equipped with autocannons—have staked Beijing's claim to the islets by circling them on a near-daily basis, often anchoring in their territorial waters for days.

It is just one of several potential flashpoints in Asia involving territorial disputes between China and its neighbors.

Li, the Chinese government official, said Beijing's new map had "serious political and strict legal nature" as well.

Why China Will Reclaim Siberia

“A land without people for a people without land.” At the turn of the 20th century, that slogan promoted Jewish migration to Palestine. It could be recycled today, justifying a Chinese takeover of Siberia. Of course, Russia's Asian hinterland isn't really empty (and neither was Palestine). But Siberia is as resource-rich and people-poor as China is the opposite. The weight of that logic scares the Kremlin.

Moscow recently restored the Imperial Arch in the Far Eastern frontier town of Blagoveshchensk, declaring: “The earth along the Amur was, is and always will be Russian.” But Russia's title to all of the land is only about 150 years old. And the sprawl of highrises in Heihe, the Chinese boomtown on the south bank of the Amur, right across from Blagoveshchensk, casts doubt on the “always will be” part of the old czarist slogan.

Like love, a border is real only if both sides believe in it. And on both sides of the Sino-Russian border, that belief is wavering.

Siberia – the Asian part of Russia, east of the Ural Mountains – is immense. It takes up three-quarters of Russia's land mass, the equivalent of the entire U.S. and India put together. It's hard to imagine such a vast area changing hands. But like love, a border is real only if both sides believe in it. And on both sides of the Sino-Russian border, that belief is wavering.

The border, all 2,738 miles of it, is the legacy of the Convention of Peking of 1860 and other unequal pacts between a strong, expanding Russia and a weakened China after the Second Opium War. (Other European powers similarly encroached upon China, but from the south. Hence the former British foothold in Hong Kong, for example.)

The 1.35 billion Chinese people south of the border outnumber Russia's 144 million almost 10 to 1. The discrepancy is even starker for Siberia on its own, home to barely 38 million people, and especially the border area, where only 6 million Russians face over 90 million Chinese. With intermarriage, trade and investment across that border, Siberians have realized that, for better or for worse, Beijing is a lot closer than Moscow.

The vast expanses of Siberia would provide not just room for China's huddled masses, now squeezed into the coastal half of their country by the mountains and deserts of western China. The land is already providing China, “the factory of the world,” with much of its raw materials, especially oil, gas and timber. Increasingly, Chinese-owned factories in Siberia churn out finished goods, as if the region already were a part of the Middle Kingdom's economy.

One day, China might want the globe to match the reality. In fact, Beijing could use Russia's own strategy: hand out passports to sympathizers in contested areas, then move in militarily to "protect its citizens." The Kremlin has tried that in Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia and most recently the Crimea, all formally part of other post-Soviet states, but controlled by Moscow. And if Beijing chose to take Siberia by force, the only way Moscow could stop would be using nuclear weapons.

There is another path: Under Vladimir Putin, Russia is increasingly looking east for its future – building a Eurasian Union even wider than the one inaugurated recently in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, a staunch Moscow ally. Perhaps two existing blocs – the Eurasian one encompassing Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – could unite China, Russia and most of the 'stans. Putin's critics fear that this economic integration would reduce Russia, especially Siberia, to a raw materials exporter beholden to Greater China. And as the Chinese learned from the humiliation of 1860, facts on the ground can become lines on the map.

see and click below

No comments:

Post a Comment